Spirits Lifted By A Tree

Crises of health, economy, climate, justice

Weigh heavily on our minds

One keeps on the lookout for

Helpful mental finds

Ken Burns in his series on “National Parks”

Presents mental find for all to see

Chiura Obata’s life-long lifting of spirits

From a thirty-seven-hundred-year-old tree

© Forrest W. Heaton 12 August 2020

Chiura Obata (1885-1975) was a well-known Japanese-American painter whose story caught the eye of Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan as they developed their acclaimed book and film “The National Parks: America’s Best Idea.” Obata emigrated from Japan to the U.S. in 1903, going on to become a renowned artist, primarily of nature in the Sierra Nevada. From 1932 to 1954, Obata was a faculty member of the University of California at Berkley and, during World War II, was interred at Topaz Japanese-American Internment Camp, Utah, for a year. This became a period of struggle, conflict and inspiration for Obata.

We believe if you were to use this brief write-up as encouragement to learn more about Obata’s life, you would find inspiration from his work and words as well. Speaking about his work, his granddaughter, Kim Kodani Hill, had this to say about her grandfather in the Burns film: “One subject that he loved to paint again and again was the sequoias. For him they were the great vertical line that connected heaven and earth. And for him he saw the life of a person in these trees. And no matter the storms and trials of life, these trees survive with great dignity and great strength.”

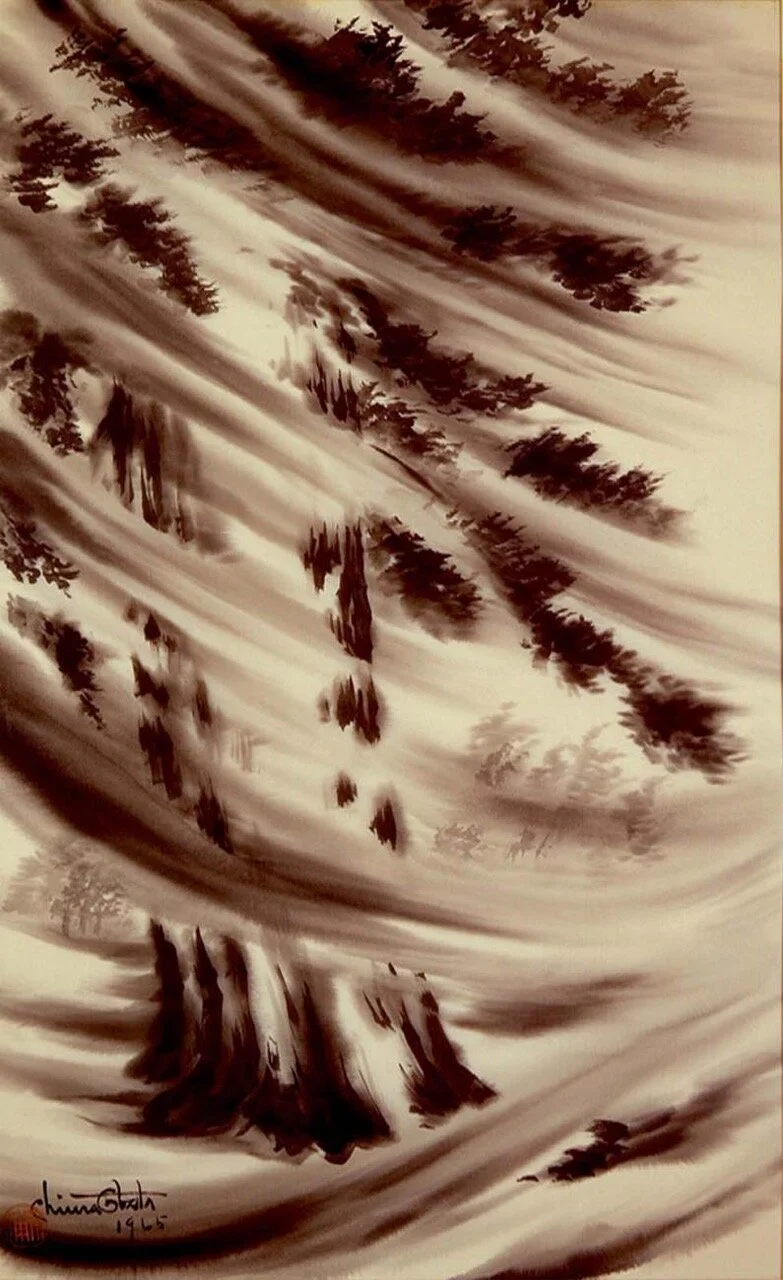

“Glorious Struggle”

Chiura Obata, Glorious Struggle, 1965, sumi on silk, 36 x 22 inches, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

(Dayton Dalton in Burns film) “Years later, in remembrance of his struggle, Obata would paint “Glorious Struggle,” the image of a tree in Yosemite’s High Sierra whose own struggle to survive seemed to give him strength and hope in his darkest hour.”

(Smithsonian American Art Museum) “In Glorious Struggle a sequoia forest endures a violent storm, an image of fortitude and perseverance Obata hoped would inspire younger generations of Japanese Americans. He described the picture’s symbolism in a 1965 lecture:

“Since I came to the United States in 1903, I saw, faced and heard many struggles among our Japanese Issei [first-generation immigrants.] The sudden burst of Pearl Harbor was as if the mother earth on which we stood was swept by the terrific force of a big wave of resentment of the American people. Our dignity and our hopes were crushed. In such times I heard the gentle but strong whisper of the Sequoia gigantean: ‘Hear me, you poor man. I’ve stood here more than three thousand and seven-hundred years in rain, snow, storm and even mountain fire, still keeping my thankful attitude strongly with nature – do not cry, do not spend your time and energy worrying. You have children following. Keep up your unity; come with me.’”